Before we announce the winners of the 2010 My Theatre Awards, we’re proud to present the My Theatre Nominee Interview Series.

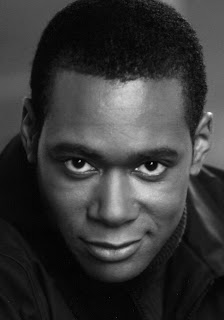

When I reviewed the Stratford Shakespeare Festival’s 2010 production of The Two Gentlemen of Verona, I cited Dion Johnstone and his costar Gareth Potter as “the inarguable top of the young-leading-man pyramid at Stratford”. My Tempest review called Dion “one of the greatest talents on stage at the festival in recent years, making his way through many of the most challenging roles ever written”. These aren’t overstatements. Since his 2007 turn as Edmund in King Lear, Dion Johnstone has been on my radar as a Stratford favourite. His performance as Caliban last summer was extroardinary, earning him a 2010 My Theatre Award nomination for best supporting actor.

One of my favourite performers in Canada, Dion is the 24th and final member of our 2010 My Theatre Nominee interview series. The passionate and candid actor took a good deal of time out of rehearsing for Western Canada Theatre’s current production of W;t to talk to me about his greatest roles, his approach to acting and how the 2011 Stratford season is shaping up.

Read on for my full conversation with Dion:

I used to read comic books in a big way when I was a kid. My mom and dad wanted to make sure that I was getting into classical literature and plays, great novels; not just superheroes and Archie and Jughead and all of that. There was a flea market near our house and they found these comic books called “Classics Illustrated”. They had stories- Julius Caesar was my first introduction to Shakespeare, The Three Musketeers, 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, Moby Dick– all these great novels were put together in a comic, an illustrated form. That was my first real introduction to literature and to drama. And it immediately connected for me into the comic book realm, which has all this fantastic imagery.

So a few years later when I was in school and we started studying Shakespeare in English class, I already had the images in my head. Most kids really struggle with the phrasing and the language, it’s just very hard to get any pictures in your head, I automatically had them.

I remember as a kid I would go to this after school program that my parents put me in before they would get back home from work. I was the oldest kid there, I hated being there, then the staff said “well, we’ll give you big kid responsibilities. Why don’t you put on a play, like a Christmas production?”and I was like “oh that would be awesome. That’d be fantastic.” So I put together a Three Musketeers that was based right off the comic book. I wrote it out and adapted it into a script form, then it was my first directing project. I must have been about 9, 10 years old at the time. So, it’s crazy enough, but it’s comic books that first got me into acting. That gave me the insight into the world and from there it all sort of just took over, whether it was acting or playwriting or directing.

Not anymore. I did a lot of that when I was a kid. In my junior high and into high school, I wrote about 4 different plays. I grew up in Edmonton and the regional theatre there used to have a festival every Spring called The Teen Festival. And what they would do is anyone in their teen years from all the high schools could audition as actors, as musicians, as playwrights. If they chose your play it would be workshopped and usually one of the plays would be chosen to have a full production. And they were always doing new plays by the local playwrights… So we as high school kids were getting the full on experience of what it was like to be a professional actor, because we were in the big theatre with professional playwrights and directors. And then being reviewed in the press and all that as well. So that was a fantastic experience for me in terms of jumping right into the profession.

At that time I was doing a lot writing and directing. One of my plays was actually workshopped through that process. And when I finished doing the Teen Fest and I graduated and thought “well, where do I want to go with this?”, I felt like I had my finger in too many pots all at once. I wanted to just focus on one and become really good at that and then from there I would sort of branch out again. I choose the acting because, being an actor, I felt like I could do it all. I used to be an artist and a musician and I thought “one day I might play a jazz trombonist, one day I might play a cartoonist”. It felt like through the acting I got to touch on all of the realms. And I’ve always felt that eventually an actor makes a really good director because they know how to communicate with actors. And they also could make a really good writer because they know the inner workings, the kind of motivations that a character needs in order to be successfully played. So I thought “that’s what I’m gonna start with” and that’s what I’ve done up until now, ever since then, is focus on the acting. And I think in time- I’m just waiting for the muse to descend once again- I’ll get back into the writing aspect of it. But at the moment I’m content with acting.

Stratford came at a point when I was working in Vancouver. I’d been doing a lot of film and television… and theatre- I had a pretty healthy balance between the two. I wanted to shift over more predominantly into film and TV. So I went to LA and had about a week there where I met with various managers and agents. And when I came back, I had a sit down with my agent to discuss the fallout and if it was the right time to go. And she said “I know you have a lot on your plate right now but here’s another bee for your bonnet- you got a call from Stratford, they want to fly you out and audition you for the next season”. But they needed to know right away, because the weekend was coming up and they would want to book it on the Monday of the next week. So I thought “wow, this is completely the opposite direction of where I wanted to go, but I’ve always wanted to do Stratford”. I just never wanted to come in spear carrier to the left and work my way up, I thought “I’ll go and build a solid film career then come back and play Othello”, [laughs]. But here was an opportunity to meet the festival and to audition for them just sort of handed to me, and I thought “I at least have to go and see what’s on the table and see what’s possible”.

So I came out and auditioned for them. At the time they were looking for someone to replace an actor in Peter Hinton’s The Swan Trilogy. They had had another performer the year before play this role and, for whatever reason, he wasn’t coming back for this season. So they were looking for a replacement. But they needed an actor who also was good with classical texts because they needed to build more than just one play for this person. Some of the directors I had worked with in Vancouver for Bard on the Beach, Miles Potter was one of them, and Scott Wentworth, I believe it was Miles who put in a good word and said “you know you need to look at Dion out in Vancouver, I’ve worked with him out there and he’s very good with classical texts”. That’s how the call came in.

So I did the audition and it felt pretty good and they asked “what are your intentions?” and I said “in all honesty, I’ve been looking towards just doing film and TV solidly” and they said “okay, we just need to know if there’d be any interest because if we pitch you a season, are you gonna take it?” And I thought “oh, okay, we’re talking serious now”. “Well, absolutely, if you offered me a season I would definitely take it into serious consideration, knowing that I wouldn’t be able to do film and TV right away”. And they said “okay, great, thanks”. I thought that was that, then within a week, they’d offered me my first season, which was dynamite. It was playing Mister Stowe in Part 2 of Peter Hinton’s Swan, and then playing Orestes in the Agamemnon/Electra trilogy that we did: The House of Atreus. A beautiful first landing at the festival.

It’s been a push and pull ever since, to be honest. Immediately after that year, I was asked to consider auditioning for the [Birmingham] Conservatory. And I felt from that year, working at the festival and seeing the incredible talent that they have there, I had all these questions about the craft of acting that I wanted answered. I felt that I wasn’t getting those answers in film and TV. So I was like “yeah, I need to do the Conservatory”. Then the Conservatory led right into my second season there, which was another season of great and very challenging roles for me at the time. I thought “I’m learning so much here. Every role, every part that I get, every season that I’ve done is just moving my craft forward exponentially from what I’ve been experiencing before, I can’t leave. I’ll leave when I feel like either I’m not as excited about the season I’m being offered, or something really big has come my way and I need to make a way to do that”. But other than that, I can’t really complain. As long as I’m learning at this kind of level I’m gonna stick with it.

So it’s made film and TV difficult to get to.

I took a year off to do Lord of the Rings [the musical]. That was a very exciting and heartbreaking experience all rolled into one. Then I came back after that and did King Lear with Brian Bedford and I played Tom Robinson with the late Peter Donaldson in To Kill a Mockingbird. At the end of that year I felt “okay, I’m done”; I’d invested a lot in theatre, there was a big changeover happening in the company, I wasn’t as excited about what had been offered to me and I really needed to get back to film and TV (I still had a burning desire to do that). So I took that year off and moved back to Vancouver. But that was the year of the writers strike so I thought “you’ve gotta be kidding me”. It was this crazy free fall. But I was able to nab work, I did about 3 or 4 different projects. So that was good, I got through the year, but it was nowhere near the running that I’d had when I left. It was just a brutal year for the industry.

The festival came back to me at the end of that year with the offer to work with Des [McAnuff, the new artistic director) on Macbeth, play opposite Colm [Feore], which was really exciting, and also to play Oberon [in A Midsummer Night’s Dream] and be in [Julius] Caesar [as Octavius]- so I thought “those are dynamite roles and it’s really a new festival, I’d like to experience what that’s like and be part of it”. So I came back 2 seasons ago. Then the offer to play Caliban [in The Tempest] came up and I was like “well, it’s Christopher Plummer [as Prospero], that may never happen again, it’s amazing that it’s even come”. So yeah, I felt that it’d be groundbreaking for me.

Working with Brian Bedford was amazing. He’s a master as an actor. It’s just an amazing process, the way he’s able to both direct and be in the production that he’s in, he’s got a fantastic system for that. So I would have a lot of one-on-one sessions with him where he would coach me on phrasing or standing positions, physicality with the language. I’ve got a very natural instinct with the language, which is very exciting and very me and I need to keep that, but there’s also a classical structure to this language that needs to be observed or else it doesn’t fully come to life. And that’s everything, whether it’s pitch, whether it’s speed. That’s the biggest thing that he encouraged, he said “you might not get it in this part, and that’s okay. If you make it a lifelong goal of your career, the you’ll start to see some real magic happen”.

Brian really blessed me with variety. You need to really explore variety. If you start on one pitch, you want to come in with a different dynamic. If you start loud you want to come in soft. If you start slow, you want to speed it up. It’s a push and pull within the structure of the form that makes it come to life. And sometimes it can be arbitrary. It doesn’t always have to follow a logical progression. He would say “it’s like the rhythm of a heartbeat, as long as it’s moving up and down, there’s life. It’s a flatline if it’s all moving at the same pace and tone and it dies”. Unfortunately a lot of naturalistic acting, and in film an TV, a lot of language is played on that level, a flat monotone. You’ve got fight against that.

Edmund was a tough part for me. It was fun with his duplicitous nature and really getting to play off Gareth [Potter] (who played my brother Edgar in it), playing off Scott Wentworth (who played our father). It was great finding those shifts and turns and dynamics between when he’s lying and when he’s being upfront with the audience. But at the same time, I found it really really challenging sourcing his degree of [villainy]. The only thing that Brian said was “don’t make him hotblooded, make him coldblooded. This is a guy who can do evil things, terrible things and not have any emotion attached to it”. He’s like Dexter. So I remember that season being a struggle for me to really isolate where that lies. The part grew over the season for me, but it wasn’t an easy fit from the get-go, it was a real challenge.

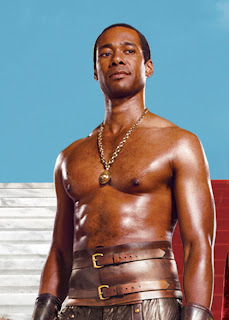

That was fun. I had so much fun in Dream. It was really empowering. Oberon, his look and style, shifted quite a lot through the rehearsal process, it was really a sort of collaboration. Originally, they had me done up in a slightly mod style, he sort of looked like Prince, in a sense, with ruffles coming out of his collar and sleeves with a black leather jacket. Then when we put me together with the rest of the fairy realm (who were all much more of a dirty, grungy look), it just looked a little bit too much. So they started paring everything away, adding the tattoos and everything. I wanted to give him edge, the authority that he’d have as the leader, and the strength between him and Titania- whether it’s the strength of the love or the strength of what happens when they’re fighting, which no one wants to be around. I also wanted to incorporate an athleticism into him, (I’m not a dancer in any realm like when you go see the musicals- those are amazing artists), but the main objective of the big fallen tree in the centre of the stage was that it represented our realm, we needed to be totally comfortable on that platform. The trick for me was trying to make it fluid and athletic- this is his world, it’s dirty, grungy, sexy, there’s a strength to it, a straightforwardness to it. The language is all in rhyming couplets, it’s got to be heightened but I wanted it to be grounded at the same time. I didn’t want it to go into “oh, listen to the mellifluous sound of his voice and not to what he says”. So I just tried to bring some edge to the guy.

That was interesting. We had no idea, prior to coming into rehearsals, what we were gonna do with it. Then, when we were presented with it, the challenge was “okay, to what degree is this Africa?”. I was looking things up, we had research videos on the war that was happening in Rhodesia at the time,… But Des was very adamant that “This isn’t Africa, this is Scotland. So it’s as if we’re combining the two worlds to create a make-believe Scotland. But you can’t let it leave your mind that the world that we’re in is Scotland, even though Scotland looks like Rhodesia in the early 1970s”. He didn’t want us to get too far into the exact politics of that time- because it was gonna take us off the play- just use what works from that realm to enhance the text. The setting and the dressing and the costumes from the time- let that do it’s work.

So my task: I love the military stuff and all that, I love any opportunity in any role to do any kind of fights. We were working with a militaristic blended form of Kalis, which is a Filipino sabre art with a machete. So that was really exciting, to take on something new.

But the bottom line was the sourcing. I’m not married, I don’t have children, I need my imagination to really extend to carry the weight of finding out the information that my wife and all my children have been slaughtered by, I now realize, a mistake that I made, even though all my intentions were for the best. I put the country ahead of my family and, because of that choice, they were left defenceless, and now they’re gone. “How do I take that on?” was a big question for me. I struggled with it all summer, because you hit a point where you go “this is incomprehensible”. And I think Shakespeare’s written it in such a way, what I got most from it was that Macduff doesn’t know how… part of what he goes through is shock, he has to ask 3 or 4 times: “are you saying, my wife?… let me just run that… my children?”. It takes awhile for that penny to finally land. So I think Shakespeare, at least part of it, is saying that people don’t know how to react when faced with information like that. Not everyone rages and screams and storms right away. I felt that, for Macduff, his story doesn’t end with the end of the play. He says “okay, I’m gonna take this, I need a second here to breathe, but then I’m gonna take this and use this as a weapon and, for their sakes, I’m gonna take down this man.” And that was my feeling, that when all this is done, there’s still a reckoning that has to happen between Macduff and God. the history continues, and it’s not a happy one. So, honouring the weight of what that must be, and trying to go there each time, it’s a real challenge, it was very difficult. Especially because I don’t have, thank God, that sense memory to draw from. So I was just trying to do everything in my power to do it justice. It’s such a turning point in the play. Of all of the death that happens in the play, that’s the most striking, it’s incomprehensible.

You see, it’s funny. It’s interesting because I think Caliban is on his own hero’s journey. I think, despite what is said about him and despite his primitive nature, (having been born from a mother who’s a witch and a father who is some sort of demonic being, so he’s not fully human) he’s still written with some of the most endearing human qualities of anybody in the play.

I started working in a real creature direction at the beginning of rehearsals. And Des said “that’s fantastic, all of the physical stuff that you’re doing. But it’s also amazing that quite often Shakespeare’s most horrible monsters that he might create, they sometimes say the most human things. And sometimes it makes you wonder who’s more the monster- the supposedly acceptable characters or the one that we term as the monster?”. And I really tried to take that to heart and find where it is, Caliban’s level of innocence. Because no one really ever, in Shakespeare at least, gets off the hook. Even when there’s a happy ending, there’s always at least some little sour note to it or the potential for it to go wrong. At the end of As You Like It, Jaques is looking at all the couples and giving them his blessing, and there are marriages in there where you go “I don’t know how long this is gonna last”. He never makes it cut and dry.

So I looked at Caliban as though he’s fighting for his freedom. Prior to Prospero and Miranda coming to the island, this was his home. We certainly get the sense that he didn’t have his mother there for him, he didn’t have anybody. So they came and showed an interest in him and he gave all the love that he had to them, showed them the island- all the best locales, all the danger points, everything-, he essentially gave his home to them, and because of an action that he committed (which, to him, was perfectly natural- it’s difficult for him to understand the wrong in what he did), he’s cast out, condemned and made a slave. So I think he has feelings of being betrayed and having his freedom taken away from him- his rights, his land, his home, and the love, I think is the biggest thing. At the very beginning when he first meets with Prospero, he tells him “I showed you all these things, and, man, I loved you”.

I think the key thing for him is the absence of love. All the love that was given to him has been, for reasons he doesn’t fully understand, taken away. Then what he does is he meets Stephano and Trinculo and he transplants all that love, that he was giving to Prospero and Miranda, onto Stephano, thinking “this is the guy who can help me to my freedom”. Then he learns a lesson along the way of what it means to truly seek for grace.

The way that Des directed our production, he allowed for a moment at the end where Prospero and Caliban have a brief moment of acknowledgement as Prospero is giving his farewell, as if to say “now the island is finally yours, you’re finally ready to lead”.

Yes. Yes! I loved that moment. That, for me, that’s what completes his hero’s journey. So, rather than playing him as a villain,- there are so many different angles and ways of looking at the play- Caliban is sort of the rejected son, the rejected child in this little family relationship that they’ve had. Whereas Ariel has been the chosen one, in a sense. Ariel is of the air, Caliban is of the earth, they’re the creatures of the island that Prospero comes into contact with and he has them both under his service.

There’s a reckoning for Prospero as well, and if Caliban is straight up a villain, then there is no reckoning for Prospero, there’s no reason for Prospero to look at his own actions and go “maybe I had some wrong in this. Maybe my judgements or the way that I looked at him, what I put on him, didn’t allow for who he innately is. So finally, that acknowledgement of Caliban at the end is my acknowledgement of Caliban as my own. It could be as my son, or it could also be as a problem that I’m also responsible for having created. I accept responsibility for my actions in this relationship”. I find that more interesting than just a straight up villain.

And Caliban does speak some of the most beautiful poetry in the play. When he says “this island is full of sounds, noises”- it’s a gorgeous aria. So somewhere in there is a beautiful, vibrating heart hidden by the twisting of his form, his body and the anger that he feels.

This is another one of those situations where you don’t know where or how it’s gonna be set until that first day of rehearsal. So in all of my prep work I was wondering “what are we going to do? Are we going to focus on the colonial aspect and capitalize on the fact that we’ve got a black actor playing Caliban? Do an island sort of theme, it’s been done before and there’s lots to explore there. Or are we going to go with the creature realm, put it more in the fantastical?” So that very first day of rehearsal when I saw the design, which was striking to look at- half human with not even full skin formed over the raw muscle, and the other half very very reptilian-, I was like “woah, okay, we’re diving in”.

The big thing for me is I didn’t want the costume to dictate the part. But, at the same time, I wanted to craft a performance that would inhabit the costume, so that by the time we hit the end and I put it on, you could see a really different being up there on the stage when the costume and the actor and everything was one. So that’s what I was shooting for right from the first day of rehearsal. I’d done a lot of work in sci-fi realm, a lot of Stargate episodes when I was in Vancouver. At one point I played a character named Chaka who was an alien creature and we had the full prosthetics- the lenses and the latex and all that- and the transformation was amazing. But that’s for film. It’s very different on stage, you’re going to be using different materials and you can’t necessarily get that same degree of cinematic believability. At the same time, you only have to do a few moves on camera and you’re doing it for a lens, that could completely convince people that you’re an alternate being. But on stage it’s three dimensional. So that was a big concern.

I wanted the performance to be strong enough that the costume would just be another layer that was put on top of it but wouldn’t overshadow Caliban. So I was happy. I felt very comfortable in it. It was a body suit that was formed right to my own measurements. There’s only a few things I would’ve changed- like the head piece. I noticed as we did the show and I was getting more agile with the physicality, my head was getting locked in there, I couldn’t turn left or right easily. I would have built a head piece almost like a cowl so it was shaped right to the scull as opposed to being one piece that zips all the way up. So little touches like that. Although I think what they did artistically and practically was magnificent. But you spend your time and you go “yeah, this would make it even a bit easier”.

The lenses were tough, and I had an option on that. If they didn’t work, I wasn’t expected to wear them. We started using them in tech and they were really difficult to put in, your eye naturally wants to reject them. But then gradually I started building up a process. They would be the first thing I had to put in, because your hands have to be clean, and then you can’t touch your eyes after that. So they’re in before I put on the makeup. I’d put them in, then put on the body suit, then I’d start the makeup and then I’m locked in until the end of the show. And your eyes don’t breathe in them, so my eyes would be raw after the performance. But I developed a way where I could get them in in one shot and out in one shot and I wouldn’t wear my actual lenses, I’d wear my glasses, so they would heal, so that was fine.

The other thing was visibility- it’s like acting behind a gauze. And there were days in the heat of the summer where the makeup wouldn’t even stay on my face for the entire scene. I would spend more time offstage in between each scene trying to cool down and get the makeup back on before I’d get back on stage. So there were times when it was literally running into my eyes in the middle of the scene and all I could see was the shape of the person (usually Geraint Wyn Davies [as Stephano]), I couldn’t see his eyes or what was going on. Those days were frustrating, but that was in the heat of the summer. But I learnt the show that way- I knew where the edges of the stage were, I knew when I was in light, I knew when I was out of the light, I knew physically how many steps things were behind me if I was walking backwards. I had a strong physical awareness of where I was on the stage at all times, so I never got too close to the edge where I was like “okay, I’m losing perspective”. I was never actually worried of falling off the stage or walking into an object or anything, and that never happened, through the entire run of the show, I never had any sort of physical injury because of limitations in vision.

But those were things that were okay probably because I had done Stargate and been through the rigour of that kind of stuff. (You can’t even eat when you’re in latex, you have to get things through a straw because if you get grease or anything on the lips, it all starts to come off. you’re in between takes in the trailer with fans blowing on you and you just go to a magical zen place and try not to let your heart rate accelerate. Then you blow it all out on the take and then you completely go zen when it’s all done). So I used a lot of those techniques to just keep myself safe through The Tempest. I think we had one day, I think it was press day, we were shooting sequences and I had to have my lenses on right from the beginning for a 4 or 5 hour period. At that point I just pulled them out, there’s no point in being a hero when it’s your eyes that are involved.

It was a physical relief. Because Valentine and Proteus and that whole world, it’s very upright. Being crouched over and sprawled and basically doing a show in a hunched position, your body needs the opposite. If you do too much of that you run into physical difficulties. So having that balance in the season, being able to have a couple days off while I played Valentine was great on that level alone.

But it was also a challenging role for me. It took a long time for that character to fit. I wasn’t getting where that guy was coming from. I couldn’t put all the pieces together- his confidence, his ability to lie. He’s very different from Proteus but both of them are able to say whatever they need to say in the moment to get off the hook. And meshing it all together with the vaudevillian world, I just couldn’t see the whole picture. So I spent maybe the first third of rehearsals going “I’m hoping this works, I’m trying but I just don’t see the picture so I just can’t put his skin on me”. The only thing I felt really confident in in those early rehearsals, we’d do our rehearsals for the tap routines, the soft shoe that we recorded that got played at the beginning of the show- the physical stuff I felt confident in. I thought “this is a realm that I understand but I just don’t know how to sew all of this together and become one guy”. And I think the turnaround came for me the day that we actually shot all the video. It was the first day that we had our full costumes, saw what the characters looked like, saw the two of us together, we did our routine and watched the playback- all of a sudden I was like “ah, there were go”. And then the confidence kicked in. Then from there it became a whirlwind. It was really exciting. I wasn’t running around wondering “Am I hitting the right notes? Are the piece falling into place?” I just started to play it. And it was in the letting go of that and just the playing of it that I started to just have a lot of fun. And all the emotional arcs and everything just started to fall into place. So by the time we opened and through the run of it, it just became a really joyous experience and I was very grateful to have it, especially in contrast with The Tempest and Caliban. But it wasn’t easy, it surprisingly wasn’t an easy building process.

We did this thing with our director, Dean [Gabourie], the first couple of days. He sat us down and we did an exercise which he calls “the continuous monologue”. Basically you start with the first person who speaks and they speak all of their lines without a break as if they’re the only person who speaks in the play- from the top of your lines to your final line. Meanwhile everyone in the cast and company (directors, voice coaches, etc…) are all sitting at a round table jotting down anything that comes to mind as you speak. Then at the end of it we go around the table and everyone pitches in what images they saw, characteristics that they saw, feelings that they had, anything. Whatever they thought, they pitch it and you jot it down. It’s phenomenal what you learn about the effect that your character is having on various people. Because we will approach a role, and not even be conscious of it, from our own sensibilities. So there are things that are naturally going to land with us that we pick up and that’s what we’ll go to, as a starting point at least. But here I was hearing the flip of what I thought Valentine was about. It was like “what?!” Most of the guys in the room were like “I don’t trust him, he’s just a little too slick with the words. I just don’t really believe the guy, I don’t know why, there’s just something shifty about him”. Then all the women, well, most of the women were like “I love the guy, he just seems like the best boyfriend in the world, he reminds me of my husband”. So wow, what complete opposites. So then what that did was it gave me like a grab bag of different colours, different qualities, different things that I could play with. And also shorthands- Dean would be like “I need a little more of this, remember what so-and-so said?” “yeah, yeah, I remember that, that quality. Okay, great, cool, let’s try that”. I’d never done that before. So because I was Valentine and he says the first line in the play, right from the get-go it was like “wow, there are so many potential things here”. Then add the vaudeville world, we were working to understand how the frame all went together. It took a bit before all those pieces dropped in.

That’s one of the great things about that play and about us. We first met doing the Conservatory together. That was his first year and the winter of my first year, and since then a lot of the major roles that we’ve played have been opposite each other. Not a lot but some of them, like King Lear for sure, The Scottish Play [Macbeth] for sure. So we’ve got a shorthand. We’re definitely brothers. We’ll be roommates next year actually. He’s a beautiful human being, an extremely talented actor. I marvel at what he’s able to do. It’s always exciting when you’ve got a solid enough friendship or working relationship where you can push each other because you’re not questioning where it comes from. You pick up on each others’ breathing and all of a sudden you find yourself going “wow, this is cool, how did we do that?”

Gareth’s an actor who likes to change it up. When we were doing The Scottish Play we’d be doing the Malcolm and Macduff scene [4.3] and his character, there are so many different layers to Malcolm- why is he testing Macduff? How much of what he’s saying is actually true about himself and how much of it is completely made up? How much is Malcolm already a savvy politician who’s willing to provoke Macduff regardless of personal feelings?- and Gareth sort of systematically went through and explored all of them. Every performance that we’d do, I’d have no idea who was coming at me. And it’d piss me off! It’d get me really angry with him at times and I would harness that in the realm of the situation (being really frustrated and upset at this guy who was our only hope, and had had such an amazing father, wanting him to take up the charge and be our leader and yet being dumbfounded that this was actually who this guy was in reality). Gareth has this ability to really drive me, and half the time I didn’t really know “where are you coming from? Honestly, where?!”

Sometimes you meet phenomenal actors but you just don’t have any chemistry together, you have to really work to finding a mutual space of agreements and trust, trust is a big thing. But I’ve got that with Gareth, so it’s always exciting to see what happens in the scene and with the characters. I guarantee he’ll be doing something different when I come back on stage. You can never trust that what we did last time will necessarily happen this time. And that’s great, it pushes me, it keeps me growing. I’m always seeking through the run of the season to get to the centre of the essence of what it is I’m playing. I’m always saying “yeah, that’s deeper… that’s deeper still, deeper still”. And hopefully by the time I’m done I can go “yeah”. Well, with Shakespeare you never hit it, but hopefully I can get to a place where I can say “that felt good”. Whereas Gareth can get to that very quickly and then go “I’m gonna try something totally different, I’m gonna try something totally different, I’m gonna try something totally different.” So he’s very much transformative and it’s cool. We work well together.

Yeah, I played Orestes my first season. It was crazy actually because I’m adopted so I have 2 mothers- my birth mother and my adopted mother. And I have very intense emotions with both, loving but also complicated. And in the Agamemnon, mostly the Electra and The Flies portion, there are scenes where Orestes has come home, he’s learned who his mother is (he’s been raised completely different, not even knowing what his true identity is) and there’s a scene that is a confrontation with the mother. Karen Robinson was playing Clytemnestra, and there were points in rehearsal where I could have sworn I was talking to my birth mom. Karen literally transformed in my eyes into my birth mom. I felt like I was a kid facing my mom, and all of the anger and frustration about past events, I had the text to come through, to deliver. Then in the run of it, my mom and dad (my adoptive parents) came to see the show, and their seats were in the aisle (we were in the studio theatre, so it’s all very intimate), they were in the seats just above the vom. And we were staged in a diagonal where I was upstage and Karen was downstage, so just above her head was my mom. We had this confrontation scene where I just let her have it, and I could feel my mom taking this information as if I was talking to her. And I thought “no, this is just a play”, but I do very strongly identify with that kind of role. So that was an easy fit.

I’ve had seasons where I’ve gotten to see everything and then seasons where I haven’t seen anything because I feel swamped by the work, but I do try to find time to go. Last season was a tough one for me, I did try to see all the plays that were on the roster or all the ones that I wanted to see, but it wasn’t the best year for that for me.

I saw the opening of As You Like It though. What an experience that was. Because it was the first time that the cycle has turned over- you’re no longer Orlando, I mean, you are, you’re part of the history of the Orlandos- but this is the new Rosalind and Orlando. I thought they were beautiful, just lovely together. And it was exciting to get to see a completely different take on the show in the festival theatre (where we had performed it) and to really feel like it was a passing of the baton. “Wow, that’s what it feels like”. Because you look at Lucy Peacock, who’s a former Rosalind twice (at least) at the festival and here she is, part of this production. That’s what actors feel like who have enough history that they have two or three versions of the same play in them. You start to realize the history of that stage. So that was really exciting for me.

Well Pete Donaldson I would say is at the top of that list. To find the words to explain what an incredible loss it is to our community is very difficult. He was an incredible champion for me, an incredible leader to look towards in terms of “that’s the kind of actor I want to be”. He would watch rehearsals, not afraid to challenge the director, always for the sake of “we want to find the most actable, the most useful answer. We can’t leave any stone unturned because if we do, by the time we hit performance we’re spending the entire season with these questions. So we need to go through this now.” So he really, through example, taught the lesson of the degree you have to stand for your character, for your scene, ask those questions, “yeah, but why am I doing this? Why am I going here? What does that accomplish? Okay, let’s try it and see if it works”.

I remember during To Kill a Mockingbird, he was great to me throughout that process. I was really nervous, I was like “there were times when I just don’t want to go there”. I would as an actor but something in my body said “I just don’t want to go through it. And no matter what I try to do to move myself through it, I just don’t feel emotional. And the stakes of this trial are huge, so I’ve got to bring something right?! So what do you do?” I would sit in the warm up room and do my meditation, try to get myself to feel sad and sometimes the more that I did that the less response I’d get. So I’d run through all my triggers and nothing worked anymore. And he said “well, that happens. Honestly, that happens, especially when you look at the runs that we do- some days you just don’t feel it. But what you have to do is just trust that you’ve done the work and if you’ve done the work it’s there, innately it will always be there. You may feel it this way one day, that way another day, it doesn’t matter, it’s there. So if you’re not feeling the urge to cry, let’s say, or you can feel a breakdown coming, rather than focus on that or focus on trying to get yourself to be emotional, focus on the opposite, focus on ‘I’m not gonna be emotional’. And sit on that, try to bury that deep inside you. It’s a weird visceral thing that happens- the audience watching your struggle to not go somewhere, struggle to keep something down, tells them that what you’re sitting on has got to be pretty deep. And quite often it makes them emotional in spite of themselves because they can feel the weight of what you’re trying with your life not to express. That often is more powerful than outright crying”.

That was like a paradigm shift for me, it suddenly takes a huge responsibility off of what I thought my job was as an actor. It’s great when it’s film- you get that trigger and you get that take and boom! And you have a couple different triggers over several takes and they’ll cut them all together and create a performance that you didn’t even give. And it makes people say “wow, how did he do that?” But that’s a very different thing from when you’re working in rep and you have to do it for an entire summer, and you’re rehearsing 2 other plays. A different skill set has to then come into play.

[Peter] was very frank, very honest, very open. And then you would see that in his work; you could see his ability to get right to the core of what the matter is, no adornment, absolute frankness. I think that’s the kind of actor we all aspire to be.

I would also say Bernard Hopkins is another actor and mentor, a friend whose work I just adore and whose friendship is really appreciated throughout the time that I’ve been at the festival.

In all honesty, I didn’t find out what the offer was for quite some time. The announcements were coming out and I was reading “so-and-so’s doing that, so-and-so’s doing that” and it was kind of a waiting game.

For me it’s always a matter of really wanting to get back into film and TV, so I have to weigh each offer- “is this the time to go?” Because I do want to be building a profile in that industry too so that, say, 10 years from now when I’m in my 40s, I can have a career where I can float back and forth between the two quite seamlessly- that’s the goal that I have. I think Colm has done it brilliantly- he has his home right across from the festival, he can come back and play fantastic parts, he’s working all over the world and he has a very solid film and television career. So I’m always working to make sure that I’m growing as an actor but I’m also laying the tracks for the career that I want. I come at it from that standpoint so I have to see what the offer is so that I can start my process.

And I didn’t find out for quite some time. I think maybe they knew what it was but they were waiting to see all the other pieces falling into place. They needed to see who their director was, I don’t know the inner workings of all that. But then from the time that I found out, then I was like “okay, wow, Aaron [in Titus Andronicus] is awesome. I’ll also be playing Lord Grey in Richard III, I’ve done Richard III before at Bard on the Beach and played Richmond in it”. So I just had to weigh, in total, for another season, if the offer was enough for me to stay. Yes the parts are fantastic and it will be another great season, but I just came off of a truly awesome season and it might be good to just go to film and TV and get that going. So I brought what I was wrestling with to Des and he said “we understand that and when you need to go, obviously we’ll be very sad, but know you’ve always got a home here. But hopefully you’ll take this offer because we’d love to have you on board for this”. So I needed some time to make sure that I knew why I was doing what I was doing.

And then I was settled with that and thought “this is actually really good”. I’ve played Edmund and I’ve played Iachimo [in Cymbeline], so I’ve been able to take on those darker roles in a sense, but it’s still a facility I want more experience in. And it will be really exciting to be in Richard III and watch how Seana [McKenna] tackles Richard, to go “How does one play villainy?” Like I said, it was a question that I struggled with with Edmund throughout the season “where is the core of having this facility to do terrible things and feel completely justified in it?”. One of the things that Brian said with Edmund was “whatever danger and pain he feels about being illegitimate and what that life was, he’s gotten through the heat of it. He’s not coming from a hot place, he’s not lashing out with these actions. He’s actually able to come at it from a distance- it’s very cold, very calculated, it’s very unemotional. Search there”. So that was the goal, to be able to be detached but at the same time engaged. I think this is somewhat similar with Aaron. Obviously, the past that he’s come from contains a lot of pain in it so a lot of his actions, for him, are justified. The thought of being in this new situation where he’s taken prisoner with the Queen of the Goths and everything that happens there, having been a slave and a servant… but there’s still a detachment and a joy in what he has to do. So it makes me wonder “how much of this was he born with? The ability to not care what happens to other people. How much of this is from a direct history?”. Because you see when his child is born, all of a sudden these different colours come out. He’s almost more paternal than you see Titus or Tamora be. He’s the most paternal character in the play- the fierce protectiveness that he has over his child and the kind of life that he wants his child to have as opposed to the life that he’s led. So that’s an amazing redeeming quality in someone who’s done a thousand dreadful things.

So I went “yeah, I gotta play that, I need to take that on”. You learn from from every role that you play, it unlocks parts of you, it transforms you, you don’t necessarily become that person but it really stretches your world. Because all you have is the work from yourself, your own interpretation, what you perceive. So it was really fast but for that reason- both to be in Richard III and witness how Seana takes on Richard (who, aside from the severity of Iago, you can say Richard is the most charming villain of all Shakespeare), and then find my own path; see how Aaron, in whatever direction the director takes it, lands in me.

Not really, funny enough. I think there are lots of people who can play Aaron. “Moor” doesn’t necessarily mean black. I saw a production with a friend of mine who’s Jewish and they set it in a militarized modern setting, no question he could take on Aaron. He’s the outsider, whatever that means. I do think that there are other actors who could take on Aaron but I am very glad that it was brought to me.

I think what it really is that draws me to Aaron is trying to find out where the source of his evil is. Also this guy has a very strong sexual presence on stage and I don’t think I’ve ever played a role to that kind of degree, what does that mean? He’s also a very aggressive guy in what he’s able to accomplish. So it’s really taking on all of those qualities that I find very exciting. I think that’ll be fun. How’s that gonna happen? I love the play Titus Andronicus but I’ve never been in a production, so I’m actually really excited to see a world that goes that full tilt with this language. That’s very exciting to me too.

That being said, I played Othello once, as a young actor. It was an adaptation that only focused on three characters- Othello, Iago and Desdemona. And there’s a line that Iago says where he feels that he’s been passed up because he’s Othello “ancient”. Some editions say “ensign”, other editions have “ancient”. So we took that term to mean that Othello is younger than Iago is. And with his friendship with Cassio, they’re the young bucks who are rising up. He’s this young, brilliant general. So we capitalized on the age differences to make the concept work. But from doing that, I grew a lot through that process, as you do when you take on any of these roles, but I also realized how much I needed to learn before I could really take on Othello. So that’s something I really want to do, I definitely want to play him in the future. It’s incredible language. I can barely sit through a production of it, I find it so unbelievably painful. Just to see this man, his life unravelling right before your eyes, if they could just have conversations- why, in all of this, are they not able to have a simple conversation that could have cleared everything? And it all happens too late. I think it’s beautifully written.

So I have an attraction to Othello, I have an attraction to Aaron, but I don’t know how much of it is because they’re essentially black roles that are there in the canon to play, although that would have to be a part of it too. I’ve been pretty lucky at the festival where they haven’t spent a lot of time trying to justify why I am the characters that I play. By that I mean, when we did King John, Pete Donaldson played the King of France and I played the Dauphin. And there was no effort to try and explain how it was possible that this guy’s son was black. We didn’t bother with that.

But with some productions I’ve felt it’s been important to really acknowledge race- like when we did As You Like It and set it in the 60s. I felt that, yes the 60s were the summers of love, the way that we set it, and that was great for a certain echelon of people. But if you were black in the 60s that was also the time of the civil rights movement and really believing for yourself that “you know what, being black is beautiful, I’m gonna be proud”. There was a lot of that that was happening at the time, it was an explosive time- Malcolm X, Martin Luther King- in the 50s going into the 60s. And I felt that Orlando (whose big argument is that he feels disenfranchised) is sort of the underdog of the story. He has to go out and make it on his own and come to believe in himself on his own because others won’t believe in him and give him the gentility, the nobility that should be rightfully his. I felt that aligned exactly with what a black person growing up in the 60s would’ve been struggling with. Some plays, the worlds we set them in, race isn’t an issue. But I think if we didn’t acknowledge that in this setting, because we were specifically setting it in the 60s, there were too many people who were gonna go “Yeah, but it just doesn’t work”. So, for me, I really wanted to use my race for that play, not in any way that overshadowed the story, because we’re here to tell it (it’s like Des saying he didn’t want us to play too much historical context in Macbeth, it was just our setting).

So there’s always a balance, but I do think it has to be questioned each time, the politics of race. Even just an acknowledgment: “is this something that we’re going to use or not? Why?”. As long as we’re all on the same page, because, nevertheless, people do see race when they see productions, not necessarily in a bad way, but it’s there. Doing As You Like It, I knew it was the first time that young kids we’re seeing a black face playing a lead on the festival stage, that was new. I do believe Yanna McIntosh had played prior, years before when she was at the festival. But it was a very rare occurrence. And to have this young guy as the hero, I knew there’d be a lot of black kids out there going “holy shit, I never even thought, I would have never even considered acting as something I could do”, but they would be identifying with me. So I wanted to be as true, in the context of the world that we’d chosen, to what Orlando’s experience (what my experience, as a black man playing Orlando) would be in the 60s.

I know I’m extrapolating and going off topic, but what I’m saying is that, in a way, race is there. But I think in terms of these 2 characters [(Othello and Aaron)] that race is so embedded that there are other things to play, stronger motivations at play now for taking them on.

Off the top of my head, I know everybody says it, but something, at some point, I’d really like to play is Hamlet. And I’ve been working with this young company that works with students and we’ve been doing some scenes from that play. So I’ve gotten to explore bits of the character to show to the kids. Before even getting to really play the full text, I’m realizing that I’m able to use that experience to start to work through a deeper interpretation of how I would play him if he came up in the future. But against type, that’s a tough one, I don’t know if I’ve thought about that. Henry V is another one that I want to play, I’ve always loved Henry.

Am I game for that? Absolutely, absolutely, absolutely. That there would be a dream come true.

I think so too. The Henrys haven’t been done now for quite some time. They did do, I wasn’t there that season so I don’t remember but, I think it was Henry IV part 1 or 2, or maybe both. I think it was 4 years ago. But they really haven’t done the cycle of plays- I think Graham Abbey was the last big Henry. So it’s definitely coming down the pipes soon.

Yeah, I shot a PBS documentary on the life of William Still, who was one of the conductors of the underground railroad. He was really notable for having left an archive. He recorded everything, the stories and the histories of everybody that he helped get their freedom. And without those journals we wouldn’t know the particulars. It was a very dangerous thing that he did and an amazing legacy that he’s left. That came immediately at the end of the festival, I basically closed Two Gents, hopped in a car, came to Toronto the next day and started working on that. And that was great, it was great for me to get in front of the camera again.

I just keep honing. Also, the festival offered a class over the summer, there’s a director named John Boylan who runs an acting studio in town, he came in and did a film workshop with us. So I took that over the summer, really loved his style, and then jumped into a course with him just before Christmas here in Toronto. My goal was just to keep the skills sharp.

TV is evolving too, from the time when I was in Vancouver until now. Everything that’s happened in the industry and what TV has had to do to combat it and keep people interested- there’s shifts in styles, shifts in the way stories are being told. There’s a lot of internal stuff. You’ve got to keep brushing up your skills. So that’s always good. And that’s what I’ve often done in the off seasons in terms of film and TV because I haven’t had a big 2 year period to just do that. I usually get little gigs here and there- 1 or 2 peppered through that just keep me floating in that realm.

And I did Raisin in the Sun with Soulpepper, pretty much at the same time. We were working around the rehearsal schedule so that I could shoot, so that worked well. Then I head off to do a production of W;t with West Canada theatre [closing March 5th]. I play the young doctor in it, who’s doing his critical fellowship but he really wants to be in cancer research. It felt like an important show for me to do, and an important show for the company as well. They lost their artistic director to cancer, and W;t was one of the shows he had programmed in the season and then they found out that he had cancer. So I know for the company, for the community there, it’s a tremendous loss that they’re experiencing and I think that that play is an important way for them to honour their former artistic director and help to sort of deal with such a difficult thing. I don’t know if you’re facing it the same way but we’ve just lost so many people, especially in these last couple years. It’s phenomenal, I’ve never seen anything like it. Largely to cancer. So I go “is this the new reality that we’re walking into, that it’s increasing? We don’t know what to do. Cherish the moments that you have and make sure you let the people that you love know that you love them, because really you don’t know”.